The Art of Observation: A Physiotherapist’s Perspective

Written by Richa Jain, Nirja Shah & Shweta Bagwe

Graphics by Nimisha More

Share this article

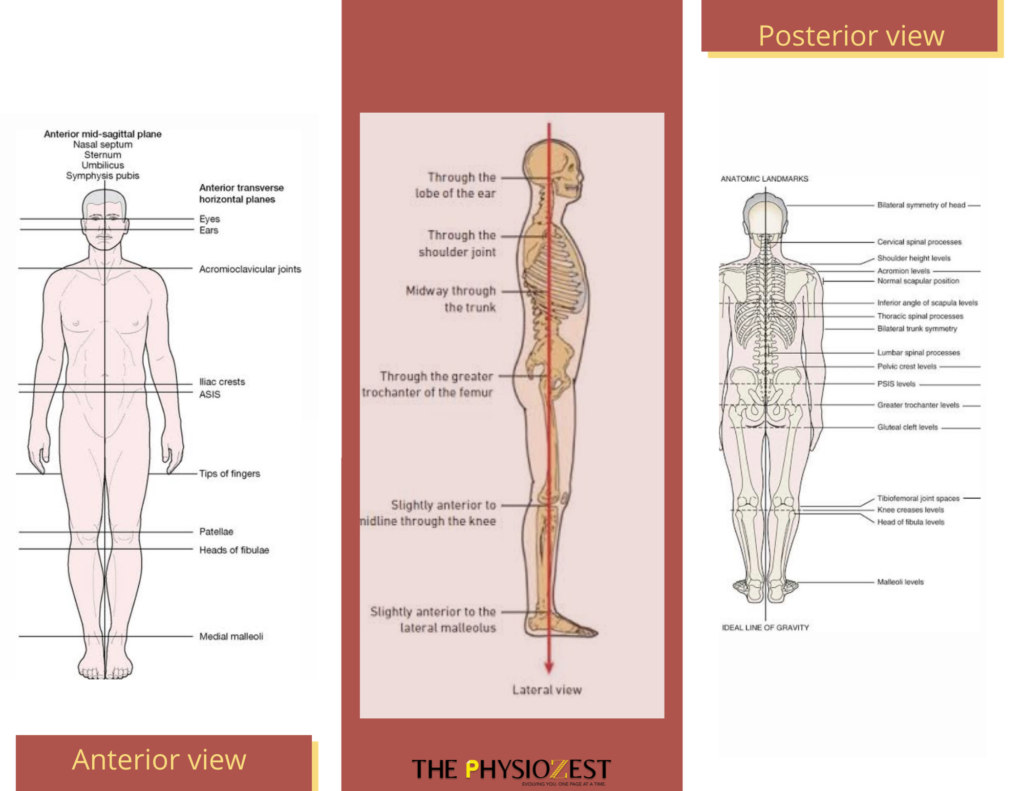

We now have a plethora of special tests and measures to determine a patient’s condition, but observation is the key to obtaining a well-rounded clinical picture. It allows you to narrow your search and avoid overlooking important factors that may be contributing to the patient’s condition. You must begin your work as soon as your patient approaches you – it is your observation of the patient that comes before speaking with them..

Movement observation is an important component in physical therapists’ diagnosis because it helps them determine which interventions are effective in improving functional abilities. Gathering, organising, and interpreting visual, auditory, and sensory data obtained while observing a moving person is part of the observation process. But there may be a few things we overlook;

Here’s to never overlooking a critical symptom ever again!

1. First Contact Observations

– The determination of the patient’s arousal level is a vital initial step, are they alert, lethargic, obtunded, in a stupor?

– Patients who are alert can provide reliable information about the somatosensory system’s integrity. Those with lethargy have lower reliability, while obtunded, stuporous, or comatose patients have none at all.

– The patient’s general posture and ability to perform functional activities such as changing bed position, transferring from sitting to standing, and ambulating to the exam room provide information about the severity of symptoms, willingness to move, range of joint motion, and muscle strength.

– Look for outward signs of pain. It can be seen as Guarding when the patient performs an abnormally stiff, interrupted, or rigid movement while moving the joint or body from one position to another, or as Bracing when a fully extended limb supports and maintains an abnormal weight distribution. Any contact between the hand and the injured area is referred to as rubbing (i.e., touching, rubbing, or holding the painful area).

– Look for obvious signs of pain, such as a furrowed brow, narrowed eyes, tightened lips, corners of the mouth pulled back, and clenched teeth or there could be Exaggerated exhalation of air that is usually accompanied by the shoulders rising and then falling; patients may first expand their cheeks.

– Therapists can gather a wealth of information about the child through clinical observations.

– Is the child motivated to explore and move around in his or her surroundings, or is he or she more of an observer and active listener who prefers to stay close to his or her family? What is the quality and symmetry of movement of the child if they are mobile? How does the child’s body react to gravity’s effects? How does the child interact with their parents and the therapist?

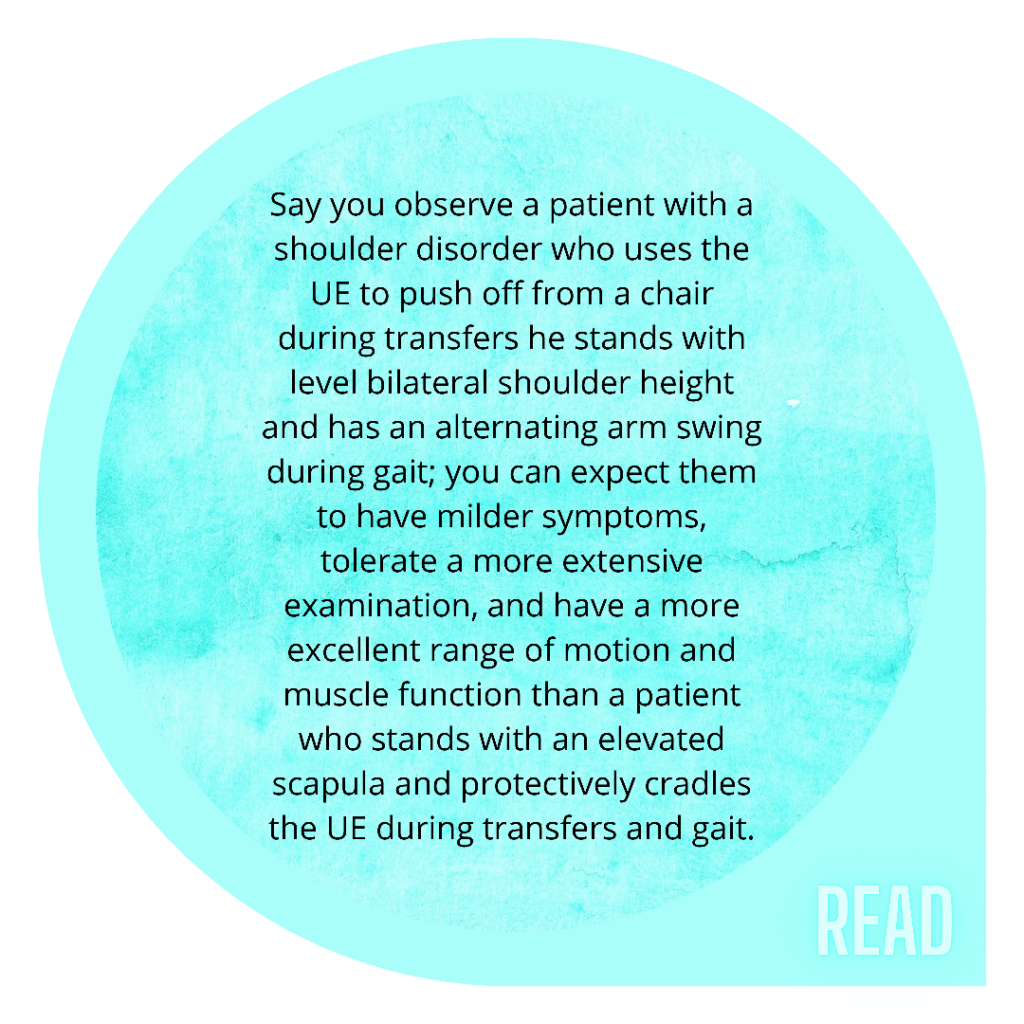

2. How good is their body alignment?

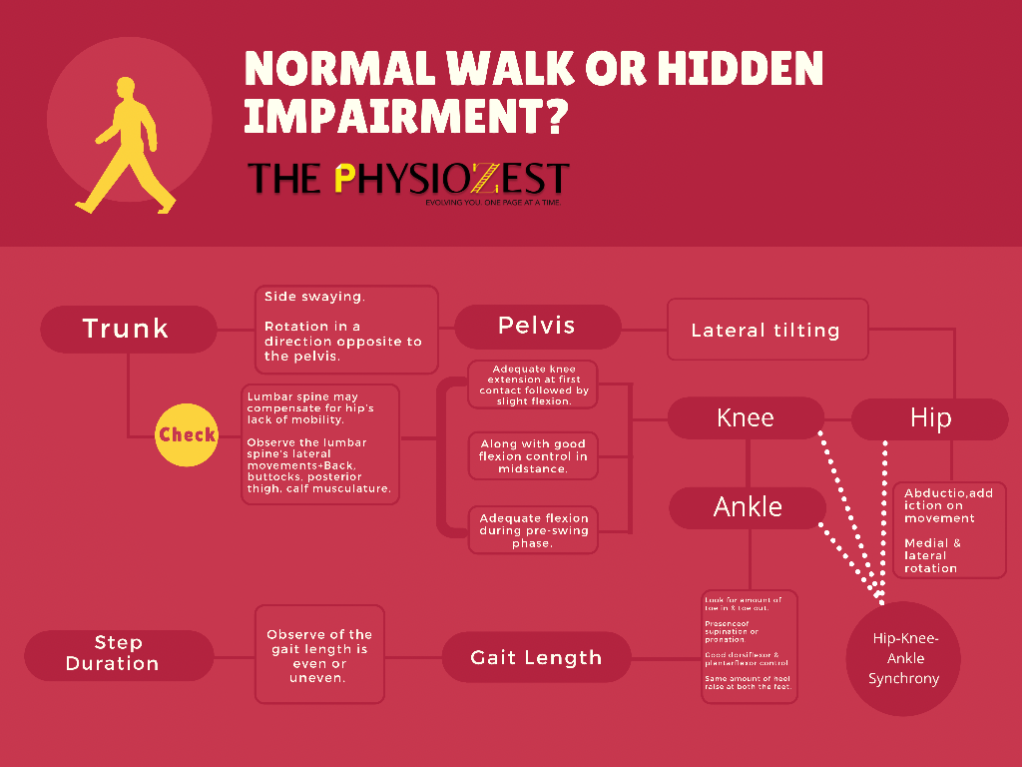

As soon as the patient stands up and begins to walk towards you, note their posture and gait, as these can point to potential pathologies. Trust me; once you’ve developed this habit, you won’t be able to stop noticing abnormalities in gait or posture – whether at the bus stop or the railway station.

Please note: Conflict of opinions regarding this point has been raised in current literature. We have come across many research papers that opine about postural changes not being a major factor in rehabilitation. We choose not to disseminate this conflict in this piece.

– The tightness can also cause alignment errors, which can manifest as anterior pelvic tilting and flexion of the hips and knees due to hip flexor tightness or posterior pelvic tilt with kyphosis and forward head in sitting due to hamstring tightness.

– The pelvic position is so important in overall body posture, the examiner should determine if the patient can position the pelvis in the neutral pelvic position; if not, there are probably hypomobile and hypermobile structures affecting pelvic position that need to be worked on.

– Alignment abnormalities that change the center of mass within the base of support place additional demands on the postural control system. For example, a stroke patient will stand with his or her weight shifted over the sound leg and away from the affected limb. Normal postural control strategies will be restricted for this patient.

3. Normal walk or hidden impairments?

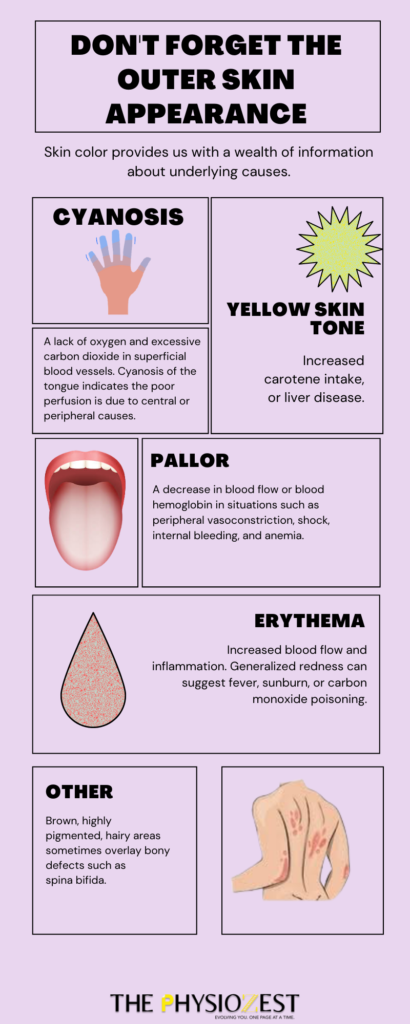

4. Don’t forget the outer skin appearance.

– You should also consider the size and shape of the soft tissues. Growth in size may indicate soft-tissue edema, joint effusion, or muscle hypertrophy, and muscle atrophy is frequently associated with a decrease in size. A loss in continuity could indicate a muscle rupture.

– Keep an eye out for cysts, rheumatoid nodules, ganglia, and gouty tophi, as these can all change soft tissue contour.

– Clubbing has been linked to cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, as well as neurovascular abnormalities.

– Loss of skin suppleness, glossy skin, hair loss on the skin, and skin that breaks down quickly and recovers slowly are some of the trophic changes caused by peripheral nerve injuries.

5. Motor Function

– Initial examination of the patient may reveal tone disorders manifested as abnormal posturing of the limbs or body. The position of the limbs, trunk and head should be carefully examined.

– With spasticity, the posturing is in fixed, antigravity positions.

– Hypotonicity can be indicated by limbs that appear floppy and lifeless.

– The therapist should examine the symmetry and shapes of the muscles, comparing and contrasting their size and contour.

– Muscles that appear flat or concave are signs of atrophy.

– Comparisons between and within limbs should be made. Is the atrophy unilateral or bilateral in nature?

– Are there multiple limbs involved?

– Is the atrophy more proximal or distal in nature?

6. What to look for when examining the patient?

– Because the lower extremities and lumbar area are so important in weight-bearing tasks, they should be examined as a functional unit. Similarly, shoulder problems necessitate examinations of the cervical and thoracic regions and vice versa.

What conditions do you believe can cause a change in body contour and alignment?

You must observe whether voluntary movements can be initiated, completed and how these movements are carried out. Take note of which muscle groups are linked together and whether the action is stereotypical or obligatory. Examine the muscle-to-muscle connections for strength. Is there any link between the upper and lower limbs or from one side to the other? Is the movement influenced by other aspects of the UMN syndrome, such as primitive reflexes, spasticity, paresis, or position?

With the help of this article, make a prioritized list of impairments and connect them to functional limitations. This method will aid in determining the patient’s progress toward functional goals and the effect of treatment. Let us work together to ensure that no muscle, tendon, or soft tissue injury falls through the cracks.

References

- Dekkers, Lieke M. et al. “Educational Programs for Learning to Observe Movement Quality in Physical Therapy: A Design-Based Research Approach.” Physiotherapy theory and practice (2020): 1–14. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09593985.2020.1712754

- Magee, David J. Orthopedic Physical Assessment. 6th ed. London, England: W B Saunders, 2014. https://www.elsevier.com/books/orthopedic-physical-assessment/magee/978-1-4557-0977-9

- OSullivan, Susan, Thomas Schmitz, and George Fulk. Physical Rehabilitation. F. A. Davis Company, 2013. https://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/books/85/

- Tecklin, Jan Stephen. Pediatric Physical Therapy. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2015. https://www.worldcat.org/title/pediatric-physical-therapy/oclc/861470504

Contributors

RICHA JAIN

Research & Content Writing Team

NIRJA SHAH

Research & Content Writing Team

SHWETA BAGWE

Research & Content Writing Team

NIMISHA MORE

Multimedia Team